When Randy Newman sang in 1990 that 'it's so hard to live' in Baltimore, few outside the 'vibrant city on the water where you will find something new around every corner' (as the city in Maryland's website puts it) knew what he was on about. Now, thanks to the sensational success of The Wire TV crime show, everyone knows that the 'something new around every corner' in Baltimore is likely to be your friendly local drug dealer, and the cops who bust him are just as corrupt as the criminals.

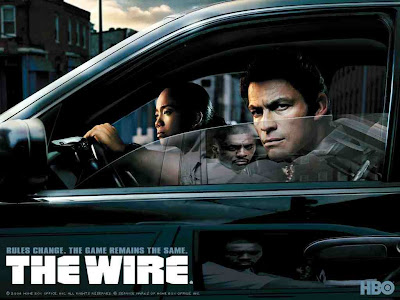

The Wire is certainly a phenomenon. At a time when the TV channels are awash with (mainly US-based) crime series, and BBC's Ashes to Ashes is puzzling all of us with its strange combination of time travelling hokum and Sweeney-style hard cop mayhem, The Wire is seemingly conquering the world (according to The Independent, the finest television show ever produced).

Not that it's garnering sensational viewing figures. The first BBC-2 series in March and April attracted a modest 568,000 viewers – though that could be because all the real fans had already seen it on the FX satellite channel, or had borrowed the DVD from their local Blockbuster or (my preferred option) the Guardian's sofacinema.co.uk DVD rental site.

To my mind, setting aside a whole evening to watch three episodes on DVD is actually the best way to understand what the hell is going on, because its multi-stranded mosaic of complex story-lines is otherwise too complex to comprehend.

However, a lot of the complexity is purely on the surface, since each of the five series majors on one aspect of life in this dysfunctional city, starting with the setting up of the eponymous wire-tap in the first series, ending with an examination of the role of the media (by one who knows, since he was a reporter with the Baltimore Sun City Desk for twelve years) in the last.

But it was the first season which set the style of all that followed. In the non-fiction documentary volume which acts as a sort of prequel to the series, Homicide – a year on the killing streets (Canongate, ISBN 978 1 84767 311 4, 646pp, £12.99), which itself was made into a Home Box Office drama, Wire creator David Simon records the way in which a real-life detective, Harry Edgerton, ('the son of a respected New York jazz pianist, [actually Dave Edgerton, a rather bland jazz café keyboardist], he was a child of Manhattan who joined the Baltimore [police] department after glancing at an ad in the classifieds'), was detached from the homicide squad to investigate drug-related killings in precisely the manner depicted in The Wire:

'Edgerton's detachment from the rest of the unit was furthered by his partnership with Ed Burns [a former Baltimore police detective and Baltimore city public school teacher, who co-authored the book The Corner with Simon], with whom he had been detailed to the Drug Enforcement Administration for an investigation that consumed two years. That probe began because Burns had learned the name of a major drug trafficker who had ordered the slaying of his girlfriend. Unable to prove the murder, Burns and Edgerton instead spent months on electronic and telephone surveillance, then took the dealer down for drug distribution to the tune of thirty years, no parole. To Edgerton, a case like that was a statement of a kind, an answer to an organised drug trade that could otherwise engage in contract murder with impunity. . .

'Two years after that initial DEA case, Edgerton and Burns again proved the point with a year-long probe of a drug ring linked to a dozen murders and attempted murders and attempted murders in the Murphy Homes housing project. Every one of those shootings had remained open after detectives followed the traditional approach, yet as a result of the prolonged investigation, four murders were cleared and the key defendants received double life sentences.

'It was precision law enforcement, but other detectives were quick to point out that those two probes consumed three years, leaving two of the unit's squads short a man for much of that time.' (Pp. 57-58)

This is precisely what happened in 'The Target', first episode in the series, except that there the narcotics squad has already been set up before the beginning, with Narcotics Lieutenant Cedric Daniels ordered to organize the detail in a somewhat half-hearted manner, and the person who stays with all the differing cast lists of the five series, the alcoholic but gung-ho law'n'order obsessive Detective Jimmy McNulty (played by the Sheffield-born British actor, Dominic West – no relation to the Timothy/Sam West acting dynasty) is brought into the squad as a result of his having spoken out of turn with a local judge.

Interestingly, McNulty's de facto boss in the fictional series bears the same name – Jay Landsman – as one of the real-life Detective Sergeants in the Homicide book, where he is described as:

'A mental case. They give him a gun, a badge and sergeant’s stripes, and deal him out into the streets of Baltimore, a city with more than its share of violence, filth and despair. Then they surround him with a chorus of blue-jacketed straight men and let him play the role of the lone, wayward joker that somehow slipped into the deck. Jay Landsman, of the sidelong smile and pockmarked face, who tells the mothers of wanted men that all the commotion is nothing to be upset about, just a routine murder warrant. Landsman, who leaves empty liquor bottles in the other sergeants’ desks and never fails to turn out the men’s room light when a ranking officer is indisposed. Landsman, who rides a headquarters elevator with the police commissioner and leaves complaining that some sonofabitch stole his wallet. Jay Landsman, who as a Southwestern patrolman parked his radio car at Edmondson and Hilton, then used a Quaker Oatmeal box covered in aluminum foil as a radar gun.

According to the official synopsis of The Wire, McNulty

“I’m just giving you a warning this time,” he would tell grateful motorists. “Remember, only you can prevent forest fires.”

'is warned by Sgt. Jay Landsman that another such stunt [such as talking out of turn to a judge], will likely leave him walking a beat in the Western District. When McNulty seems unconcerned, Landsman asks about his worst-case scenario. "The boat," McNulty says, laughing. The marine unit.'

Which actually happens in the second series, beginning its terrestrial TV airing in the UK on May 4. This switches the main focus from the drug-dominated 'jects to the Baltimore waterfront, in a sequence of 12 episodes which have echoes of Elia Kazan's 1954 Marlon Brando vehicle, On the Waterfront, though no one actually says they 'could of bin a contender'. These are perhaps the most interesting of the five seasons, since they are the only ones to allow a role for the organised working class, albeit one as riddled with corruption as the police and city hall, centred on the character of Frank Sobotka, secretary-treasurer of the longshoreman's union of checkers, the men who oversee the loading and unloading of cargo ships, and thus able to allow through the contraband shipped in by 'the Greek' (whose true name we never discover, though he himself denies Greek ancestry).

I don't think I'll be spoiling it for you if I reveal that in it McNulty has been relegated to his "worst-case" posting, as a uniformed "poh-leece" (the suffice '-man' seems to have been demoted from Baltimore vocabulary) with the Harbor Unit, described by one of his new colleagues as 'the sweetest detail in the whole damn department if you give it a chance.'

Another feature which has attracted a lot of attention, both from viewers and the media, has been the jargon. Various attempts have been made (by The Independent in UK, and the Wall Street Journal, of all people, in USA) to publish glossaries; a self-defeating process, since just as street slang changes more quickly than the rest of us can keep up with, so it goes also in this fictional representation of life over several years. For instance, at the beginning, warning cries of 'Five-oh' warn dealers and users that the police have arrived (itself a demonstration of the way, despite its protean nature, popular terminology can also lag behind history, since the Hawaii Five-O police series wound up in April 1980, more than 20 years before the first airing of The Wire, and long before these fictional characters would have been born; no doubt they had caught the re-runs, which are a feature of daytime cable in USA, as in UK). But by the time of the final series, first aired Stateside in January last year, six years after the show began in July, 2002, this has changed to 'Poh-poh', which is far less arcane.

David Simon, who created the series, follows the precedent set by William Gibson in his Neuromancer series of SF novels, of never explaining anything. We have to work out from the context that, for instance, a 'burner' is a disposable mobile phone, 'cheese' is money, and 'fiend' is a customer for drugs (from drug-fiend, get it?).

Actually the precedent goes back further than science fiction. When Shakespeare mentions 'kerns and gallowglasses' in Macbeth, he doesn't have one character explain to the other for the benefit of the groundlings, that they're talking about Irish soldiers, carrying battle-axes.

(I wonder if, when our distinguished former PM was addressed by George Bush as 'Yo, Blair', he realised his American boss was using a derogatory term applied to a street-corner drug dealer?)

Incidentally, the comparisons that have been made to Shakespeare are not so pseudish as it might seem. One of the great things about The Wire is the way in which it demonstrates the street poetry of popular speech – and especially black speech – in exactly the same way as the Bard of Avon would have done, were he working for HBO.

The writers often do this in digressive riffs, like the discussions in the ''ject' (project, or in British usage, housing estate) about the provenance of the MacDonald chicken nugget:

'Man, whoever invented these, he off the hook! Motherfucker got the bone all the way out the damn chicken. Till he came along, niggas be chewing on drumsticks and shit, getting their fingers all greasy. He said, "Later" to the bone. Nugget that meat up and make some real money.'One says to the other that if he didn't get a lot of money from the innovation, 'Nah, man, that ain't right'.

He's told 'Fuck "right". It ain't about right, it's about money.

'You think Ronald McDonald gonna go down that basement and say, "Hey Mr Nugget, you the bomb. We selling chicken faster than you can tear the bone out. So I'm gonna write my clowny-ass name on this fat-ass check for you."

'Shit. Man, the nigga who invented them things still working in the basement for regular wage, thinking of some shit to make the fries taste better, some shit like that. Believe.'

Again, this didn't spring innovatively from David Simon's brain. It's reminiscent of the dialogue between Jules and Vincent Vega in Quentin Tarantino's Pulp Fiction, about what the French would call a McDonalds Quarter-pounder.

Another such digression is the chess lesson given to a couple of yo-boys by the young drug-dealer, D'Angelo (Dee) Barksdale, nephew to the drugs boss, Avon Barksdale in the second show in the first season:

DEE: 'Look, check it, it's simple. It's simple. See this? (Holds up king.)Simon displayed his reporter's ear for speech patterns in the Homicide book. Here, a detective is trying to get a witness to a murder to testify, but she won’t even open her door to him:

'This the kingpin. And he the man.

'You get the other dude's king, you got the game. But he's trying to get your king, too, so you gotta protect it.

'Now the king, he move one space, any direction he damn choose, cos he's the king.

'But he ain't got no hustle, but the rest of these motherfuckers on the team . . . they got his back. And they run so deep, he really ain't gotta do shit.'

YO-BOY: 'Like your uncle.

DEE: 'Yeah, like my uncle.

'You see this? This the queen. She smart and she fierce. She move any way she want, as far as she want. And she is the go-get-shit-done-piece.'

YO-BOY: 'Remind me of Stringer [Avon's right-hand man].'

DEE: 'And, this, over here, is the castle. It's like the stash. It moves like this. And like this.' (Stash, I may not need to explain, as the show does not, is the storehouse for drugs.)

YO-BOY: 'Dog, stash don't move, man.'

DEE: 'Come on, yo, think. How many time we move the stash house this week? And every time we move the stash . . . we move a little muscle with it, to protect it.'

YO-BOY: 'True, true. You right. All right. What about them bald-headed bitches right there?'

DEE: 'These right here. These are the pawns. They're like the soldiers. They move like this, one space forward only . . . except when they fight. Then it's like . . . Or like this . . . And they like the front lines. They be out in the field.'

YO-BOY: 'So how do you get to be the king?'

DEE: 'It ain't like that. See, the king stay the king, a'right? Everything stay who he is . . . except for the pawns. Now if a pawn make it all the way down to the other dude's side . . . he get to be a queen. And like I said, the queen ain't no bitch. She got all the moves.'

YO-BOY: 'A'ight, so . . . if I make it to the other end, I win?'

DEE: 'If you catch the other dude's king and trap it . . . then you win.'

YO-BOY: 'But if I make it to the end . . . I'm top dog.'

DEE: 'Nah, yo, it ain't like that, look. The pawns, man, in the game . . . they get capped quick. They be out of the game early.'

YO-BOY: 'Unless they're some smartass pawns.'

'Heavy pounding on the door is answered at last by a light from upstairs, where a frame window is suddenly and violently wrenched upward. A heavyset, middle-aged woman—fully dressed, the detective notes—pushes head and shoulders across the sill and stares down at Pellegrini.Having started viewing the show, as I say, on DVD (I can't afford a FX contract), as I tuned into the BBC-2 re-runs, I began to become somewhat disenchanted, seeing the gears working under the surface.

'“Who the hell is knocking on my door this late?”

'“Mrs. Thompson?”

'“Yeah.”

'“Police.”

'“Poh-leece?”

'Jesus Christ, Pellegrini thinks, what else would a white man in a trenchcoat be doing on Gold Street after midnight? He pulls the shield and holds it toward the window.

'“Could I talk to you for a moment?”

'“No, you can’t,” she says, expelling the words in a singsong, slow enough and loud enough to reach the crowd across the street. “I got nothing to say to you. People be trying to sleep and you knocking on my door this late.”

'“You were asleep?”

'“I ain’t got to say what I was.”

'“I need to talk with you about the shooting.”

'“Well, I ain’t got a damn thing to say to you.”

'“Someone died . . .”

'“I know it.”

'“We’re investigating it.”

'“So?”

'Tom Pellegrini suppresses an almost overwhelming desire to see this woman dragged into a police wagon and bounced over every pothole between here and headquarters. Instead, he looks hard at the woman’s face and speaks his last words in a laconic tone that betrays only weariness.

'“I can come back with a grand jury summons.”

'“Then come on back with your damn summons. You come here this time a night telling me I got to talk to you when I don’t want to.”

'Pellegrini steps back from the front stoop and looks at the blue glow from the emergency lights. The morgue wagon, a Dodge van with blacked-out windows, has pulled to the curb, but every kid on every corner is now gazing across the street, watching this woman make it perfectly clear to a police detective that under no circumstances is she a living witness to a drug murder.

'“It’s your neighborhood.”

'“Yeah, it is,” she says, slamming the window.'

Let's take the title. The 'wire' is a wire-tap, and a lot of the police by-play is about how they manipulate the rules and get round them to allow them to bug the perps' phones ('perp' equals 'perpetrator', or criminal). So the whole show could be considered a very clever justification for the growth of the surveillance society, especially given that its six-year run coincided exactly with Bush's abuse of the system.

But it's the amoral insistence that in this life, everyone loses, no matter how good their intentions, that sticks in my craw. Yes, that's the way it is, most of the time, in this entropic world, but there are sufficient exceptions to keep hope alive.

Like Woody Guthrie,

'I hate a song [or a TV series] that makes you think that you are not any good. I hate a song that makes you think that you are just born to lose. Bound to lose. No good to nobody. No good for nothing.On the other hand, the sheer professionalism of The Wire as a piece of work makes me proud to be a fellow-writer, so my feelings about it are rather ambivalent.

'Because you are too old or too young or too fat or too slim too ugly or too this or too that. Songs that run you down or poke fun at you on account of your bad luck or hard traveling.

'I am out to fight those songs to my very last breath of air and my last drop of blood. I am out to sing songs that will prove to you that this is your world and that if it has hit you pretty hard and knocked you for a dozen loops, no matter what color, what size you are, how you are built.

'I am out to sing the songs that make you take pride in yourself and in your work.'

The fifth and final season of The Wire centres on the media. Simon has explained: 'It made sense to finish The Wire with this reflection on the state of the media, as all the other attendant problems of the American city depicted in the previous four seasons will not be solved until the depth and range of those problems is first acknowledged. And that won't happen without an intelligent, aggressive and well-funded press.'

In keeping with its jargon-littered scripts, this final chapter is entitled "-30-", which happens to be how print-and-typewriter-based journalists in pre-computer days used to end their stories. Nobody seems to know why, though I think it had something to do with telex machine codes.